What is permaculture?

Forget sustainability. For those who want to save the planet and all who inhabit it, things have gone too far to be sustained. Instead, attention should be given to regeneration through permaculture.

Permaculture, as a concept, sprouted in 1979 in Australia when Bill Mollison and David Homgren founded The Permaculture Research Institute around the idea of the conscious design and maintenance of naturally productive ecosystems that are diverse, stable and resilient.

In turn, these ecosystems provide humans ongoing food, energy, shelter and other material goods. The word itself comes from combining the two words ‘permanent’ and ‘culture’ to form permaculture. The philosophy behind it is based on working with your ecosystem, instead of trying to modify it or taking steps to artificially adapt it to suit your needs or wants.

In practice, according to Jesse Watson, principal designer at Midcoast Permaculture in Maine, it’s a landscaping or agricultural system that uses nature as its model.

“Permaculture is the tool and process we use that begins with looking at the wild ecosystems as a template,” Watson said. “In practice it’s a way of making decisions on what elements we put in landscaping or farming or forestry that creates an entire ecosystem that is also agriculturally productive”

In practicing permaculture, and teaching others how to do it, Watson said he stresses setting planting and landscaping goals after first observing and understanding the specific ecosystem in which you are developing with an eye toward productivity. This productivity, Watson said, includes food production by planting crops or pasture to support wildlife, forest stewardship to promote tree growth and managing habitats to promote native wildlife in a sustainable manner.

The philosophy of permaculture

Sustainability is admirable, according to Dr. Joline Blais, associate professor of new media at the University of Maine and advisor for the campus’ Terrell House Permaculture and Living Center. But it’s not enough.

“Instead of sustaining a status quo in an ecosystem, we have to start making it better,” Blais said. “We have to interact with nature in a way that builds up the natural world.”

Potential human impact on an ecosystem can be charted on a spectrum according to Blais: destructive, sustainability and regeneration.

“We have done so much destruction to this planet, sustainability is just not going to cut it anymore,” she said.

For example Blais points out it is entirely possible to sustain a fossil fuel-based economy through more efficient engineer, or a forest habitat by planting monoculture tree plantations using chemicals. But sustaining systems in those ways is not what is best for the planet.

Watson has no problem with the idea of sustainability in discussing permaculture.

“I look at sustainability being that which you can sustain over a long period of time without relying on fossil fuels,” he said. “We can certainly talk about permaculture as a movement toward resiliency, regeneration and sustainability of the ecosystem’s health.”

The permaculture footprint

Blais has been an avid practitioner and teacher of permaculture for a number of years.

“Instead of sustaining what we have, we need to be making it better,” Blais said. “When humans interfere with nature in the right ways, it really helps the planet.”

Practicing permaculture is designed to increase the human footprint on the planet, but in a way that enhances the natural world. Taking active steps toward reforestation, rebuilding soil, growing food close to the people who will consume it and then working to sustain those practices over the long term are the kinds of footprints humans should have, Blais said.

In his own permaculture work, Watson uses vegetation to create riparian buffers near streams or wetlands to shade and protect the waterways from runoff.

He advocates something called “forest farming” in which instead of clearing out existing trees and associated woodland vegetation, the farmer grows crops that naturally flourish in that environment to create an edible landscape.

“If you have an existing forest you adapt your planting and growing methods, rather than changing that ecosystem to meet your desires,” Watson said. “In forest farming we talk about ‘non-timber’ crops like mushrooms, shade tolerant edibles, herbs and medicinals.”

Permaculture designs also include rainwater collection systems using barrels, rooftop gardens that channel rainwater runoff into the barrels or swales that help filter the water runoff.

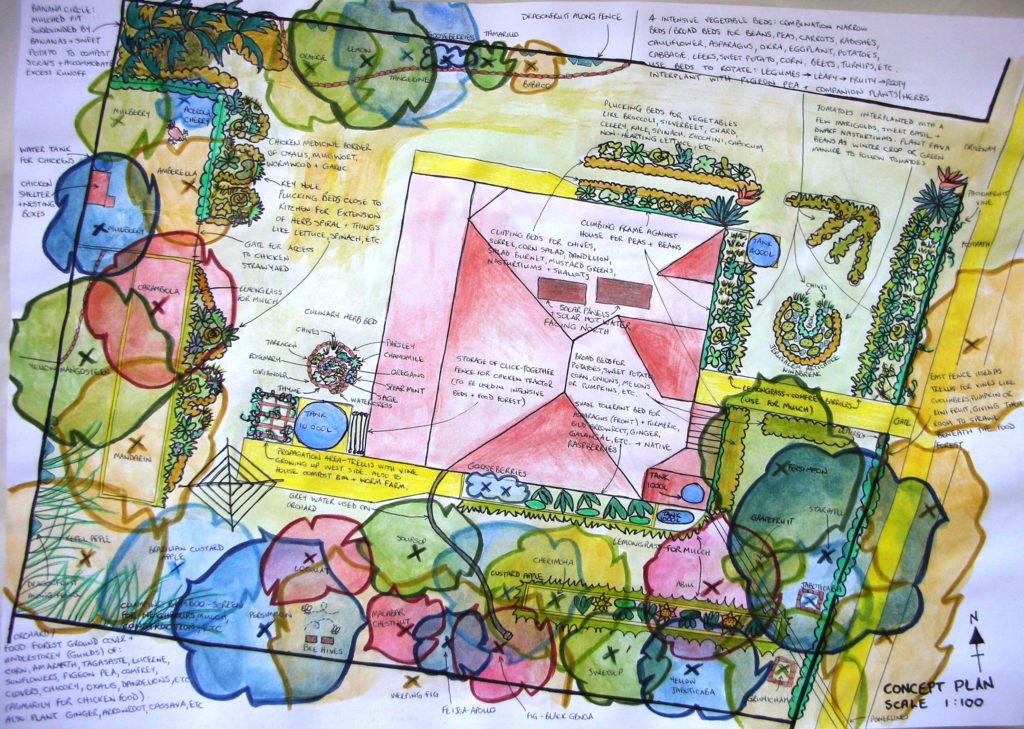

Blais suggests planting diverse gardens and crops and avoid the agribusiness monoculture model, practicing companion gardening, minimize as much as possible the use of machinery that can compact the soil and that use fossil fuel, use local and native seeds, manage water resources using roof gardens that allow water to runoff for collection, plan social areas where children can play and people can garden as a community, create habitat for naturally occurring bird and wildlife; and be willing to make mistakes and learn from nature.

“Let’s have a large footprint that actually helps,” she said.

Permaculture is work

Make no mistake, practicing permaculture is work, Watson said.

“My experience is that you get out of [permaculture design] what you put into it,” he said. “I really want to dispel the notion some people have that a ‘self-sustaining’ landscape is one that takes care of itself with no work on your part.”

But if humans are going to survive, Watson said they need to start working with and not against the natural world.

“Many of the large-scale agricultural practices today are extremely violent on the ecosystem,” he said. “It’s fine to have annual crops, but we need to put them in the right places and work with the ecosystem.”