How you can get involved with citizen science on your homestead

Your homestead is a living laboratory, and homesteaders are constantly conducting experiments and making observations. Getting involved with citizen science on your homestead takes that one step further by turning those daily observations into usable data.

In citizen science research projects, the general public contributes to scientific data by making observations in their own communities. This could mean recording water quality data or sending in soil samples or observing birds, among other things.

“I think citizen science is worth doing because it’s impactful,” said Sean Ryan, citizen science fellow at North Carolina State University. Ryan runs the Pieris Project, in which citizen scientists catch and send in invasive white cabbage butterflies to the researchers so they can better understand how the pest has evolved to be such a pervasive invasive species.

“For me as a researcher, it allows me to do science at a scale that I wouldn’t be able to do otherwise,” Ryan adds.

Homesteaders and small farmers are especially good candidates to contribute to citizen science. The daily interaction with the natural world required by homesteading (and, often, the access to sustainably managed land with healthy soils and a wealth of species), make the potential contributions to science even more valuable.

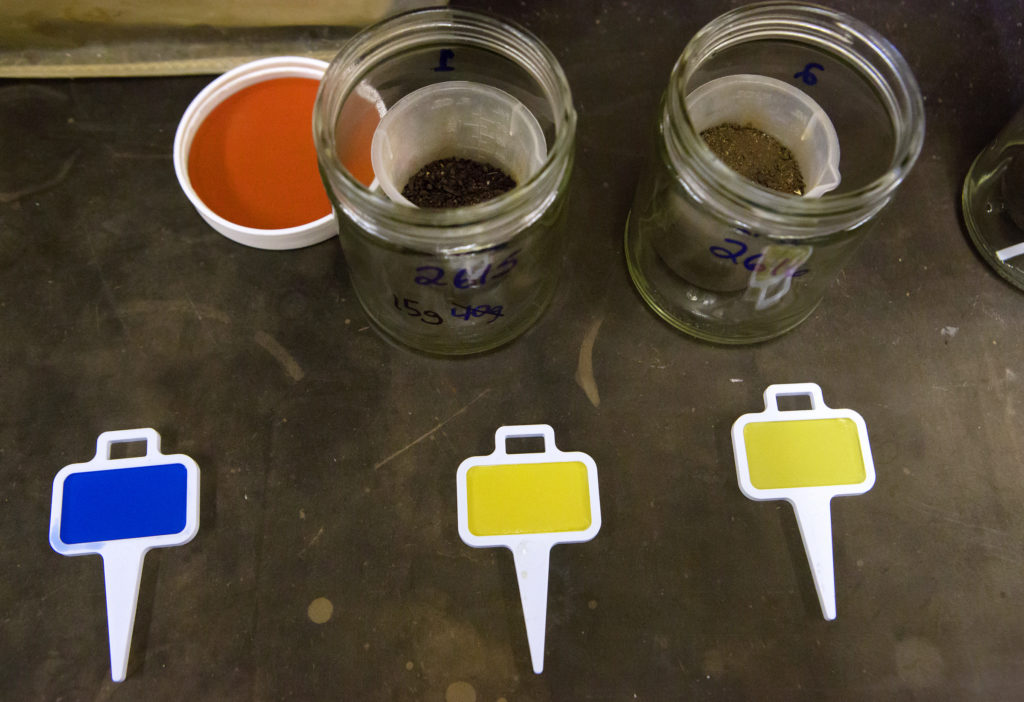

For projects like the Citizen Science Soil Collection Project at the University of Oklahoma, a connection with the natural world is invaluable. Participants send soil samples from their property for researchers to analyze the biomedical potential of the samples’ available fungi.

“I would say homesteaders have probably a greater awareness of soil and soil health, whereas we get many soil samples from yards that are well manicured and cared for,” Robert Cichewicz, program director. “I would be thrilled if people who have that level of awareness would participate in the program.”

The potential for citizen science on homesteads extends even beyond outdoor and agricultural observations. Erin McKenney, postdoctoral researcher at North Carolina State University, helps run the Sourdough Project, in which bakers who prepare their own sourdough starters can send them in order for scientists to study the different microorganisms where they live.

So far, the project has collected 576 different sourdough starters from people living in 17 different countries. McKenney is also planning to launch a similar citizen science project looking at the bacteria in lacto-fermented vegetables.

“Homesteaders are much more intune to where their food is coming from and the processes by which we get food,” McKenney says. “You’re engaging with these products as they’re being made.”

This extra awareness often leads to better data and scientific innovation. “Because they are handling sourdough all the time, [homesteaders] notice things that are really scientifically interesting that scientists might not have thought about before,” she says.

To get started as a citizen scientist, Ryan suggests trying the iNaturalist app, which lets you record observations about all sorts of species — plants, bugs, birds, animals and more — that you encounter from your phone; their projects section has a list of collaborative research efforts being conducted through the app. Zooniverse and SciStarter are also good online databases to search for citizen science projects near you.

For more local citizen science efforts, reach out to your local cooperative extension. Ryan says that sometimes cooperative extensions will even work with farmers to develop projects.

Esperanza Stanchioff, extension professor in climate change adaptation at the University of Maine cooperative extension, heads a citizen science program called Signs of the Season: A New England Phenology Project. Volunteer scientists are trained to observe and record the the seasonal changes common plants and animals living in their own backyards to fills a gap in regional climate research.

“The more that we know about how things are changing and how that affects plants and animals, the more that we understand how those things are changing, the better we can prepare for it and the better we can make decisions,” Stanchioff says.

From planting to fermenting, so many aspects of homesteading require scientific skills. By contributing your daily observations to citizen science projects, you can help inform the world beyond your homestead.