What hardiness zones mean and how to determine yours

Maybe you are a first-time gardener trying to figure out what to plant, or maybe you are a seasoned grower trying to figure out why your perennial flowers never make it through the growing season. No matter your skill level, one of the most helpful pieces of information to guide you on your gardening journey is to figure out what your hardiness zone is.

“It helps people understand what they can and cannot plant in their landscape,” said Kate Garland, horticultural specialist at the University of Maine Cooperative Extension.

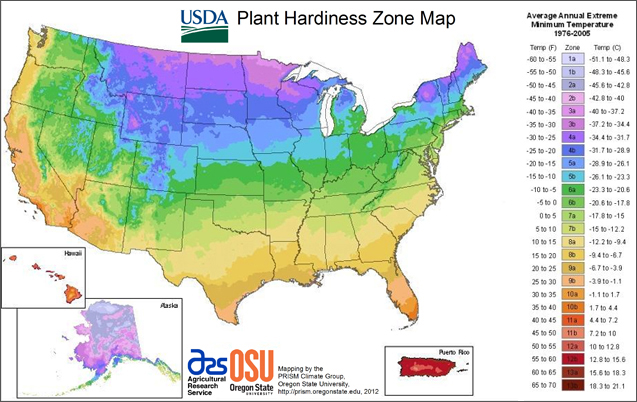

Hardiness zones were developed by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) to determine the plants that grow best in the climate where you live. Each zone represents the region’s minimum average winter temperatures.

“It is the average of the extreme low temperatures,” Wendy Wilber, statewide Florida master gardener coordinator at the University of Florida. “The USDA Hardiness Zones help us know what to grow where, allows us to select the right plants for our temperature climb and really helps us to get plants to thrive.”

The zones range from 1, which includes the chilliest regions of the United States like Fairbanks, Alaska, to 13, which encompasses warm areas that rarely receive frost like Puerto Rico. Each numbered zone has a difference of about 10 degrees Fahrenheit from one to the next.

The zones are further divided into subzones designated by letters a or b, which indicates a difference of about 5 degrees Fahrenheit and adds further nuance and accuracy between specific regional areas.

Hardiness zones, Garland explained, are most useful for determining what perennial plants will survive year-round in your area, though they are also useful for determining how well and how long annual plants will thrive.

How can I find my USDA Hardiness Zone?

The best way to determine your hardiness zone is to use the USDA Hardiness Zone Map. The online version has a feature where you can search hardiness zone maps by zip code or state. Seed packet maps are often based off of this information as well.

The USDA Hardiness Zone Map was first published in 1960, but has been updated twice: once in 1990 and again in 2012. The updated maps not only reflect changing climatic conditions — the latest edition is generally on 5 degree Fahrenheit subzone warmer than the previous one — but also more sophisticated methods for recording weather conditions with a greater number of weather stations and consideration for different geographical factors like elevation and proximity to water.

“It’s based on a lot of weather data, so it’s changing,” Garland explained.

According to the map, Bangor is in zone 5a, with average minimum temperatures ranging between -20 and -15 degrees Fahrenheit. The northernmost regions of Maine go as low as 3b and there are areas along the southern coast that classified as zone 6a.

Shortcomings of USDA Hardiness Zones

The USDA Hardiness Zone map is useful, but far from perfect. The map does not account for the nuances of factors like the beneficial effect of a snow cover over perennial plants, freeze-thaw cycles or soil drainage during cold periods.

Even so, the USDA Hardiness Zones are best at determining growing conditions in the eastern United States because the area is comparatively flat. West of the 100th meridian, the USDA zone map is less useful.

“We don’t really use the hardiness zones that much [in the West],” said Valerie Borel, University of California master gardener and horticulture program coordinator for Los Angeles County. “They don’t give enough information on the different climates because there are so many smaller microclimates within smaller areas.”

The geography of the western United States plays a role in the USDA Hardiness Zones’ failings.

“Within the Southern California Basin area, we have mountains that are 11,000 feet high, and then less than 100 miles away we have the ocean,” Borel said. “It one compact area, you’re getting a wide variety of geographical areas.”

The greater variance in elevation and precipitation across the mountainous and geographically varied West confuse the hardiness zone algorithm. Lush, coastal Seattle, Washington, and the inland desert city of Barstow, California, for example, are both considered hardiness zone 8 even though their weather and plants are much different.

Even if you are not in the West, the USDA Hardiness Zones can fail to show the geographical nuance on your property.

“Just because you’re in a warmer zone doesn’t mean you’re in an easier growing climate,” Garland said. “Coastal towns in warmer zone suffer from having a cooler growing season. There are definitely some very, very windy sites that might cause tissue dieback.”

Wilber explained that your microclimate can also be influenced by how your property slopes and how much canopy cover your property has. She recalled a friend with a mountain property where the front yard is zone 9 and the back is 8b.

“The zones work, but you also have to understand the microclimates on your own property,” Wilber said. “They’re ballparking it but you need to figure out what’s going on on your own land.”

Alternatives and supplements to the USDA Hardiness Zones

There have been some attempts to make up for the shortcomings of the USDA Hardiness Zone designations in the West and beyond.

Sunset Western Garden Book developed a climate zone map with 24 different climate zones for the Western United States.

“They took it upon themselves to come up with a system that happens to be more reliable and is a better indicator than the hardiness zone,” Borel said. “A lot of people consider it the gardening bible.”

In order to account for high temperatures as well as low American Horticultural Society’s Heat Zone Map divides the country into 12 zones, which are based on the average number of days per year that a region experiences temperatures over 86 degrees Fahrenheit. Damage to plants from heat is more subtle and slow-burning than damage from cold, so the map is especially useful if you are looking to plan perennial plants in warm climates.

Chill hours, which measure how long the cold temperatures last, are also important for growing things like fruit. The traditional definition of a chill hour is any hour under 45 degrees Fahrenheit, though there are competing theories and models.

“For our deciduous fruit crops, considering chill hours helps trees get cooling they need in dormancy,” Wilber said. Some apple tree varieties, for example, over 1,000 chill hours, while northern Florida only gets about 600 hours.

Wilber recommends contacting your local cooperative extension to find out the number of chill hours in your area.

Even with these alternate designations, most gardeners agree that you should observe the microclimates in your garden in order to grow most effectively.

“There are microclimates all over the place, even within someone’s landscape,” Garland said. “To have a clear understanding of the warm pockets and cold pockets is a thing to consider.” She recommended planting tender plants closer to your house’s foundation to create a warmer microclimate, for example.

“People have to pay attention and figure out what’s going on on their piece of property,” Wilber added. She recommended keeping a garden journal to record temperatures and monitor rainfall.

“I’m sure there’s an app for that as well, but the apps are going to be for your area as opposed to your own property,” Wilber said. “The engaged gardener is going to [keep a journal].”