7 sustainable materials that could rock the fashion world

Between the constant churn of fast fashion and the resources expended to make new clothes, the environmental cost of fashion is staggering. Creating and processing fibers — especially fibers made from synthetic materials — often uses toxic chemicals and incorporates nonrenewable materials that wind up piling up in landfills when the trends change. Even natural fibers require large amounts of land, water and other agricultural inputs to produce. Some commonly-used fabrics are more sustainable than others, but designers still have a fairly limited swath of sustainable materials to choose from.

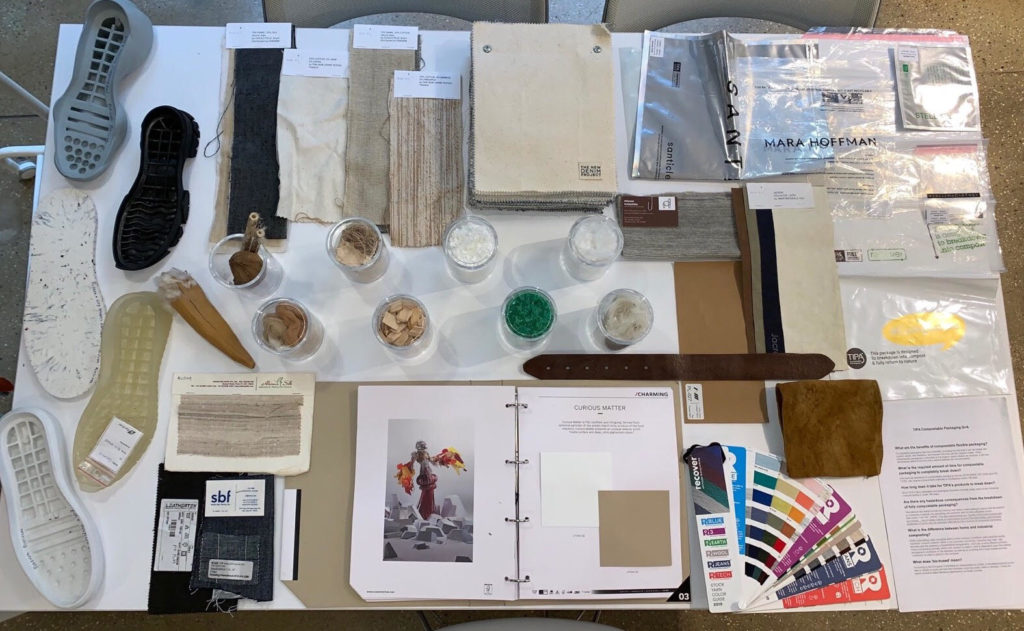

Increasingly, though, the fashion industry is looking towards innovative fabrics made from unexpected materials for a more sustainable fashion future.

“I have been doing this for 12 years and twelve years ago, nobody gave a damn,” said Kristine Upsleja, founder and president of Madisons, a Los Angeles-based fashion consulting firm focused on promoting and educating about innovative materials. “For the past three or four years, all of a sudden there is this hype.”

Experts cite many reasons for this. Upsleja credits the shift on the upcoming generation of consumers’ increasing demand for eco-friendly products, as well as influences from other industries.

“There’s a new consciousness that was created through the food industry, [natural] foods and eating healthy,” she said. “Now, it switched into the fashion industry.”

With this increased consciousness has also come a realization that the existing options were lacking. The alternatives to animal-made materials for eco-conscious vegan consumers, for example, often used materials made from fossil fuels like polyester, acrylic, nylon and spandex.

“There is a need for alternative materials that aren’t based in fossil fuels,” Tara St James, founder of Study New York, a fashion design consulting service based in New York City. “If we look at the vegan design community, they use alternatives to animal fibers and skin, [that are] based in plastics. That’s not really sustainable.”

Though many of the concepts for these sustainable fabrics have existed for generations in cultures around the world, most modern iterations of sustainable fabrics made from alternative materials are still in the early stages of development. Some, however, have been picked up by popular designers or carved markets abroad as consumers have signaled their desire for more sustainable products.

“Consumers are looking to make a statement with their purchases and being more conservative with their buys,” St James said. “They want something that has a message. To be honest, I don’t know how that translates to sales, [but] we’ll see if the demand can bear the cost.”

Here are 7 sustainable fabrics made from materials you might not expect that have the potential to rock the fashion world.

Pineapple leaves

In the nineteenth-century, Filipino royalty wore cloth made from pineapple leaves. Inspired by the tradition, the abundance of the area’s natural resources and the environmental impact of the leather goods industry, the company Ananas Anam created a material called Piñatex, a leather substitute made from pineapple leaves that would otherwise be thrown away by agricultural producers.

This sustainable material is on track to scalability. The company has already partnered with brands like H&M in order to bring their pineapple leaf leather to a mass market.

“What Piñatex is doing right now they are on a good path,” Upsleja said. “It took them a while, but they have started collaborating with brands.”

St James noted, however, that big brand partnerships have made it more difficult for other designers to work with the material.

“There’s a lot of demand for it because of its innovation, it’s also very difficult for people to access,” she said.

Upsleja also pointed out a persisting design flaw: Piñatex is still coated with a petroleum-based resin.

“They don’t use bioresin, which brings the whole thing down to not being sustainable or biodegradable,” Upsleja said. “I hope they’re working on it.”

Mycelium

The root structure of mushrooms, known as mycelium, can be used for a variety of purposes, from packaging and building materials to — you guessed it — fabric.

After two weeks of growing in the lab, the mycelium is marinated in another proprietary liquid to seal the deal and dried to the form of the clothing design. Along with being carbon-negative and closed-loop, mycelium-based materials, which are developed in a lab, are durable, water-resistant and can be naturally dyed almost any color. Depending on the exposure to light, humidity, temperature and what the mushrooms are fed, mycelium fabrics can be shell-like or porous and spongy. For designers, this means mycelium can be used for a gauzy jacket or as a substitute for leather.

“The concept is really great: not to exploit the earth, to grow something in the lab that can later be tossed and biodegrade,” Upsleja said. “It’s fantastic. I hope bio-couture and ‘Mylo leather’ will take off. I really hope so.”

There are several companies working on mycelium fabric, like Dutch company NEFFA and the San Francisco-based MycoWorks. The material also has brand-name backers. Stella McCartney partnered with “Mylo leather” developers at Bolt Threads in 2018 to develop a mycelium-based version of one of their iconic bags.

Stinging nettle

Stinging nettle grows abundantly throughout North America and temperate regions across the Northern Hemisphere. The stems and leaves are covered with brittle, needle-like hairs called trichomes, which contain a mix of irritating compounds like histamine, acetylcholine and formic acid, which — true to its name — sting those who try to pick or eat it.

Stinging nettle has long been eaten and utilized in herbal remedies, cordage and dye. When gathered with care and soaked to separate the fibers (a process known as “retting”), it can also be spun into fiber. In fact, stinging nettle was a popular textile fiber before the rise of cotton in the 16th century (it made a brief comeback in World War I among German soldiers facing a cotton storage).

St James herself has a pair of jeans made from stinging nettle.

“It’s a strong fiber, it grows naturally without the use of pesticides and it’s durable,” St James said. “I’ve seen it mostly in denim because not a lot of materials that require that durability.”

Similar to hemp fibers, stinging nettle fibers are versatile and keep the wearer warm in winter and cool in summer because they are hollow. They can be grown with far less water and pesticides than cotton. Though cultivating stinging nettle does not face the same legal problems as cultivating hemp, St James questions whether it is as scalable.

“It’s an interesting plant, but I don’t think is going to be as popular as hemp will be,” St James admitted. “Nettle is difficult to process and collect.”

Coffee grounds

Coffee grounds can be upcycled in many ways — including in textiles. Singtex, a Taiwanese company, spins processed coffee grounds with polymers (generally, St James said, made from recycled plastic bottles) into yarn for outdoor and sports performance wear.

Because of the properties of roasted coffee, the coffee-based fabric S.Café is fast-drying and boast natural anti-odor qualities and UV ray protection.

“They have huge quantities available,” St James said. “The percentage of coffee is quite small, [but] it’s still good. That one is already scaled.”

Kapok

Kapok fiber is a lightweight, cotton-like fiber found in the seed pods of the Ceiba tree (otherwise known as the silk cotton tree), which grows in wet evergreen and dry semi-deciduous tropical forests and can usually be found in Mexico, Central America and West Africa.

“I love kapok,” St James gushed. “It comes in a pod, like a cocoa bean. The short fiber is soft, smooth, warm and insulating.”

Kapok is silky, dry and natural resistant to moths and mites. Because fiber is short and brittle, it is generally not spun. However, its buoyancy and moisture resistance makes it ideal for use in cushions and mattresses. Kapok was actually used in the designs for the first life jackets until synthetic foams came on the market.

“The fiber itself is so short [and weak] that you can’t really spin it, [but] it’s great for filling pillows and down jackets,” St James said. “Kapok is a natural alternative if you are looking for a vegan alternative to down fill. You can get polyfill, but it is still a synthetic.”

Alginate

Alginate is a chemical found in seaweeds and kelps which, aside from being some of the fastest-growing, rapidly-replenishing organisms on the planet, sequester carbon and filter surrounding water.

To make alginate fiber, first the alginate is derived from seaweed or kelp and powdered. The powder is made into water-based gel, to which a non-chemical pigment is added, and it is extruded into long strands of fiber that can be woven into a fabric.

The material is strong, flexible, naturally fire-resistant and biodegrades faster than cotton without requiring pesticides or large areas of land to grow. Such textiles also claim to be soothing and moisturizing to the skin.

Companies like Algiknit aim to produce alga-based apparel on a commercial scale. Other companies that use algae, seaweed and similar raw materials include SeaCell and Vitadylan.

One of the promises of algae-based textiles, according to Upsleja, is the potential for the material to be printable (though she admitted it is still in its experimental phases).

“It’s crazy where are we going with 3-D printing, and that is another issue of fashion,” Upsleja said. “The footwear industry using it already, but there is still not a really great fiber out there you can print with.”

Oranges

Citrus rinds could prove just as useful in the fashion world as they are around the house. In 2014, Italian entrepreneurs launched Orange Fiber with the goal of extracting orange industry by-products that would normally be thrown away in order to produce a gauzy, ethereal fabric for the luxury market.

“A lot of fruit material tends to be alternative to leather,” St James said. “[In contrast], the orange fiber is taking the orange peels, which are a byproduct of the juicing industry, and converting them on a cellular basis to something similar to viscose [that has] much more commercial applications.”

In 2017, famed Italian fashion house Salvatore Ferragamo became the first to utilize the materials as they launched a capsule collection of silky orange fiber dresses, shirts and trousers.

“That one is going to be very popular very quickly,” St James said. “The demand is off the charts.”

Cactus

Cactus leather is one of the newest sustainable materials on the market — and, no, it’s not prickly. A pair of Mexican inventors, Adrian Lopez and Marte Cazarez, recently unveiled this attractive, supple and — most importantly — biodegradable organic “leather” made entirely from prickly-pear cactus from their company, Desserto.

Their company is green, but it is already making waves. In October, the founders attended the Lineapelle international leather trade exhibition in Milan, Italy where they presented the innovative leather substitute to the world’s top designers. In November, last week, Desserto showed at RawAssembly, a sustainable raw materials sourcing event in Australia, where Vogue Australia reported that they had the most buzz of all companies at the entire event.

Unlike many other sustainable materials looking to change the fashion world, the founders of Desserto are especially concerned with access. In interviews, they have expressed that they are working to provide samples for small and mid-sized to designers as they continue production.

The challenges

While many of these sustainable materials show promise, Upsleja said to consider the environmental costs of production. Turning food waste into fibers, for example, often requires significant chemical or energy inputs.

“You have to weigh what [is] more sustainable: to use the food waste that sits in landfills and creates methane gas, or [to] add the chemicals to break it down into fibers,” she explained.

Upsleja is optimistic about the potential for many of these sustainable materials, but emphasized that even the ones with brand-name partnerships are still in a stage of experimentation.

“It is all in the state of experimenting,” she said. “We are in very interesting times, but I still think we are trying to find alternatives to regular cotton [or] to polyester. I believe that one day somebody will come with something scalable, but right now everything is all in the state of experimentation.”

At the current stage, smaller designers still have trouble accessing alternative sustainable materials to experiment with in their own designs.

“All the companies are very secretive and it’s [hard] to get samples,” Upsleja said. “I am very fascinated by everything, but the accessibility is a very big downside. It’s frustrating, to be honest.”

The potential any of these alternative sustainable materials to scale up to the level of popularity of fabrics like polyester, nylon or any of the more modern synthetic fabrics that pervade the market remains to be seen. Still, the fashion industry is turning its eye towards sustainability in a creative way.

“I love this whole movement and love all the experimentation but we will see what’s going to survive,” Upsleja said.