GPS Cows teaches rural youths how farming can be high-tech

Farming has a bad reputation for being low tech. Between manually-operated hand tools and the long hours working outdoors, it can be difficult for the upcoming tech-savvy generation to imagine a future in farming. A program called GPS Cows, which integrates engineering, technology and project-based learning for rural youths in Maine and Australia, hopes to change that.

“I think that young people don’t understand the technology that’s used in agriculture,” explained Amy Cosby, senior research officer for agri-tech education and innovation at CQ University in Victoria, Australia, and co-founder of GPS Cows. “It’s a really cool for young people to see that there’s more to agriculture than all that hard work.”

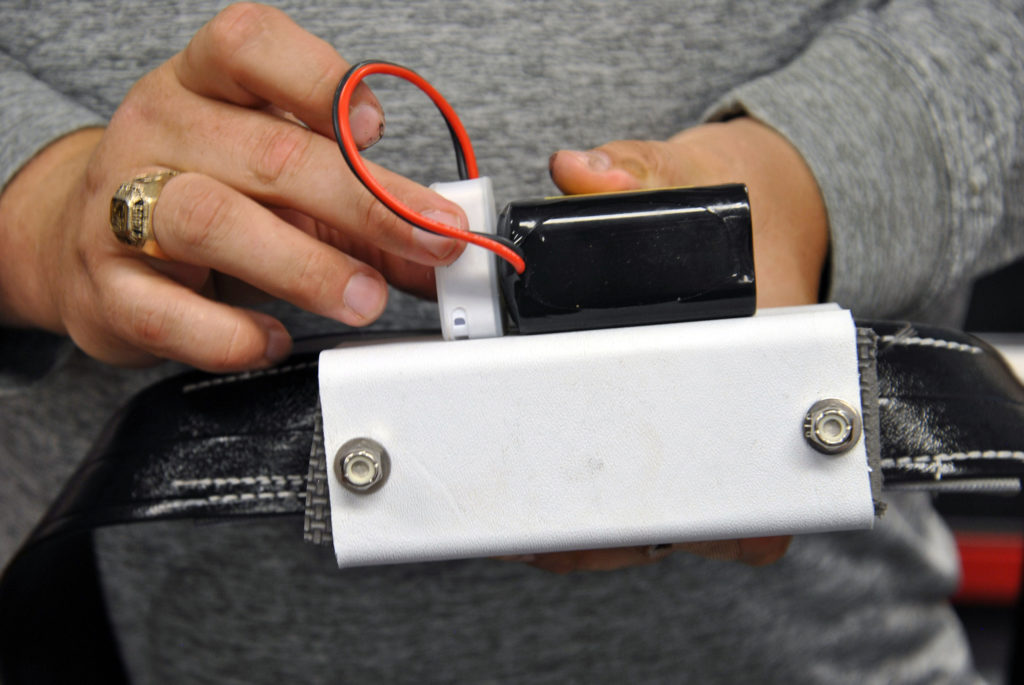

In GPS Cows, students build their own cow collars with built-in global positioning systems (GPS, for short), collect and analyze the data from the grazing ruminants and present their findings.

“Large-scale farming is increasingly digital,” said Colt Knight, assistant professor and livestock specialist at the University of Maine Cooperative Extension and co-founder of GPS Cows. “These skills transfer. The point is to improve digital literacy, not just to make a GPS collar for cows.”

A pilot of the GPS Cows program ran last year in Maine, and has since rolled out in hundreds of schools across Australia. But before the GPS collars used in GPS Cows helped students learn about data in agriculture, they helped a graduate student to conduct research on a budget.

Building the original GPS Cows collar

When Knight was in graduate school at New Mexico State University, he wanted to track gluttonous cows. A cow’s grazing behavior is genetic and inherited. Tracking cows allows ranchers to determine which cows are most self-sufficient so they can breed them and build a better herd.

“Animals are a lot like people,” Knight laughed. “There can be lazy animals.”

Optimizing the interaction between cows and the land is important, especially out West.

“Grazing land in the United States is public in the West, so ranchers constantly have to justify their existence against people who say that cattle are destroying rangelands,” Knight explained. “What most folks want to know is how to utilize the land better.”

Pinpointing and breeding efficient cows, particularly ones that are shown to use fewer land resources and respect the boundaries of endangered species, is one way to do so.

But Knight could not afford the technology to get the data he needed. At the time, he explained, researchers like him had to buy commercial GPS tracking collars that cost about $2,000 apiece.

“For researchers with a sample size of 30, that adds up,” he said.

Knight thought he could make a cheaper collar to suit his needs and asked his university for experimental funds to experiment. After some tinkering, he was able to make a cow collar with a GPS tracker for $80.

Knight admitted that the commercial collars are more accurate and equipped with several extra features, but his GPS collars were easy to build and perfect for tracking basic grazing behavior for researchers on a budget.

Developing GPS Cows

Around the time that Knight was testing his first GPS collars, he met Cosby.

Cosby, who aimed to figure out how to show young people the ways technology can be used in agriculture, saw Knight’s easily-assembled, low-cost GPS collars as an excellent, accessible tool to do so.

“Everybody uses GPS so they already have an understanding of it works,” Cosby said. “[Everybody] can use Google Maps.”

Despite the distance, the two decided that they wanted to start a program using Knight’s GPS collars to teach the next generation how technology will shape the future of agriculture.

In 2018, Knight launched the first iteration of the GPS Cows program with a handful of students from rural areas of Maine.

“We let them build a GPS collar and develop a hypothesis that they can test using their farm animals or a neighbor’s farm animals,” Knight explained.

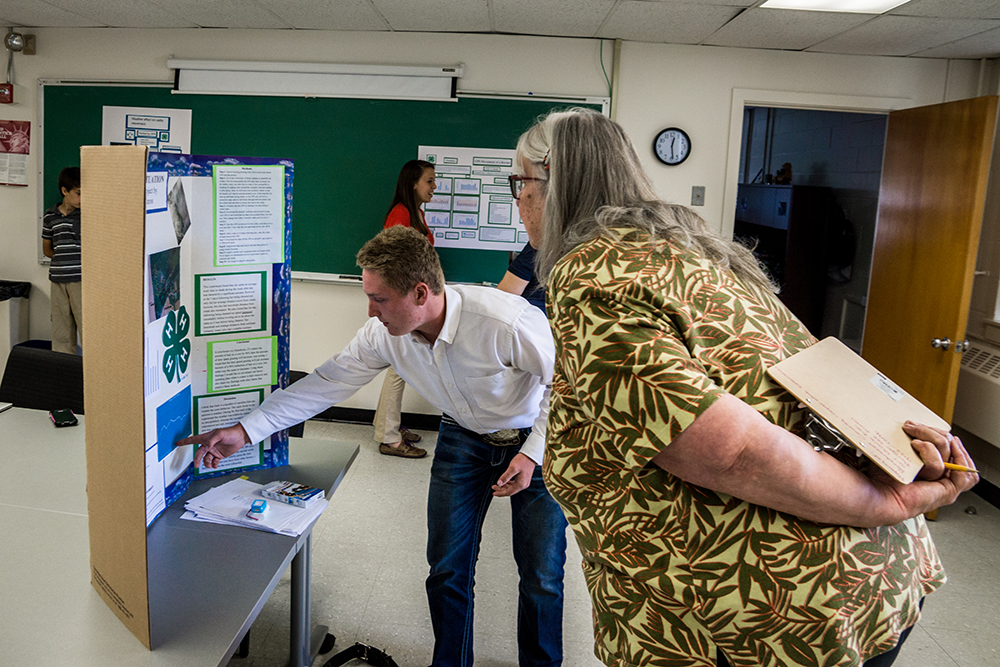

The program ended with a poster competition where the participants presented their findings to the general public. Last year’s winner expanded his project and took second place in the Maine state science fair.

Bringing GPS Cows to Australia

GPS Cows recently rolled out in over 200 schools in every state and territory of Australia. The pilot program in Maine helped inform the newest iteration of the program.

“We learned that it does excite students,” Cosby said. “We learned that we had to simplify some of the activities and provide guidance.”

In Australia, for example, students with practice data before they build their collars and collect their own data.

“It’s pretty hard to analyze data, and there aren’t answers all the time, so we get them to analyze a known data set first,” Cosby explained.

Unlike the GPS Cows program in Maine, Australia’s GPS Cows curriculum is taught through schools.

“We don’t have 4-H and things like that,” Cosby said. “If [students] going to participate in the GPS Cows program, it’s going to be through school, not an extracurricular.”

Some Australian schools do have an advantage of American schools, though: school farms.

“A lot of schools have school farms so they have their own animals that they can track themselves,” Cosby said. “If they don’t, a lot of them are working with local farmers.”

The future of GPS Cows

Cosby and Knight both predict that as agriculture continues to digitize, programs like GPS cows will become increasingly relevant.

“As cheap as electronics are getting, we’re going to see more and more high tech farms,” Knight predicted.

Encouraging more interest in agriculture is also important to addressing shortages of farm labor.

“Getting good labor is an issue,” Cosby said. “By doing programs like GPS Cows, we can encourage people to be involved in agriculture.”

Right now, though, Knight just hopes to fill his GPS Cows class this year. He is still seeking participants — the program will start when he gets around 20 participants, and the time frame is flexible — and interested students in rural Maine can contact him to sign up.

Once those students sign up, they are in for a little healthy international competition.

“Colt and I would really like to have a competition [between GPS Cows classes] — Australia versus U.S. — for developing research and those kinds of things,” Cosby laughed.

Cosby and Knight hope to expand GPS Cows beyond Australia and the United States.

“Colt and I would like it to be a worldwide platform for young people to share their data and ideas and realize that agriculture is a really exciting, viable industry,” Cosby said.